Most days, there is a little note taped into the journal with information about sending fruit for fruit salad day or donating decorations for the classroom. I admit that after the first week, I became a less attentive reader of these notes. Bad mama.

So, yesterday, I decided to catch up and came across this message from Monday:

I felt baffled as I read this note. I have been working as a nurse in the Congo for almost 2 years now. I felt like I knew a lot of French health vocabulary. Surely I should be aware of the name for the common, "very contagious" disease that was sweeping my daughter's school.

"Des oreillons." Nope. Nope. No idea.

So, naturally, I asked Mama Vida and Mama YouYou, who began to clutch their ears and puff our their cheeks, moaning and miming what must be an awful disease. They kept insisting that "des oreillons" happens all the time,"if one person in the house gets it, everyone does,"and "the cheeks get very swollen...you know!"

They couldn't understand why I was being so dense. I had no idea what they were talking about. I could see their respect for my medical opinion sinking a couple of notches.

Finally, I conjured up a black-and-white image of a sick kid with a cloth tied around their ears. Kind of like this:

|

| Image from here. |

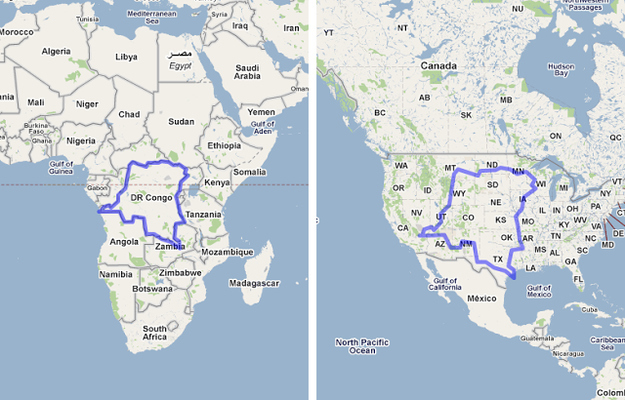

Mumps. A disease I have never had nor seen. A childhood illness made rare in the United States by the MMR vaccine. One of those nasty things that exists as part of normal life here in the Congo.

Hopefully, LouLou - having been fully vaccinated before we left for life in the third world - has a fairly low risk of getting this disease, even if it is rampant at her school. But it's so strange for me to feel so uninformed about an illness that Mama YouYou described as "like a really bad flu with swollen cheeks - everybody gets it at some point."

While I'm sure it appeared in my nursing textbooks, I think that my true knowledge base about mumps consists of having used the name to describe the MMR vaccine to parents right before I stuck a one-year-old in the thigh. My "broad" medical knowledge is actually so specific. So tailored to one, first-world, reality. Sure, I now know how to pop out a Mango fly larvae and I can recognize, test, and treat malaria, but those are the flashy tropical diseases. What about the mundane, everyday muck that Kinshasa Mamas must watch for in their babies. I don't know much about those.

This is a whole new ballgame. Better brush up on my childhood illnesses, circa 1950 America. I'll start here:

|

| Vintage book cover image from here. |